Sri Lanka is at crossroads. After a 30 year conflict that brought great hardships to the people and endless destruction to its built-environment, Sri Lanka has finally emerged victorious in bringing the avalanche of social, cultural and environmental catastrophes of the past 30 years to a complete halt. Today it treads along a new path with a vision for a prosperous future. Although the journey has already begun, the path is not all that clear.

By Archt Prof Ranjith Dayaratne

In this context, it is apt for the Sri Lanka Institute of Architects to dedicate its Annual National Architecture Conference – 2012 to the theme ‘Regenerating Sri Lanka: Architects and the Built-environment’. Architects have always felt the pulse of the people whose built-environments they create and recreate and have contributed immensely to the generation of spaces and places that have nourished their sense of being. This time is no different. Indeed with this theme, it intends to do more than it has ever done: to contribute to the regeneration of Sri Lanka.

In its call for contributions to this conference, the SLIA emphasises the role it seeks to play. It says, “housing, transportation and tourism sectors are seeing new and greater investments with the government embarking on several mega projects such as highways, airports, harbours and housing projects. However, for this process to be ultimately successful, the government as the major player needs to obtain the assistance of other stakeholders, specially professionals, in the development of these. The development and regeneration of the built environment would essentially require the participation of architects as visionaries, researchers and advisors at various levels of the implementation process.”

Regenerating Sri Lanka indeed is a mammoth task. First of all, we do not know precisely what should be done to regenerate Sri Lanka. While infrastructure may be developed, roads may be paved, boundary walls removed or new hotels and projects built, there is no certainty that they will ‘regenerate’ the nation as a whole.

Regenerating Sri Lanka is not a task achievable entirely either by the government or by the architects. Indeed it is a task for the collectivity of its people among whom the architects will have a significant role to play, together with the other professionals. There is a perception that the politicians will have to take the lead because it is they who are expected to represent the wishes of the people, set up policies and ensure that they are implemented. For politicians to take the lead however, the policies will need to be based on sound ideas and principles, for which the professionals have to contribute by propagating appropriate ideas and principles based on informed imaginations and tested experiences.

Before regenerating however, it may be useful to begin by asking, what is it that has degenerated?

It is no secret that Sri Lanka has degenerated socially, culturally, morally and spiritually, not just because of the enormous stress of the conflict alone, but also because of other forces that have come to influence society during the past few decades. One may take open-economy for example and see how economic competition has corrupted the age-old Sri Lankan values. Globalisation obviously is an undeniable force that has brought many a values that have negative influences upon society.

Architects however are unlikely to have much influence in changing such degeneration of society in any direct way although what they will build and what they will not build will have possible implications there too. More specifically however, architects will have major opportunities as well as responsibilities in guiding the ways to deal with what may have degenerated in terms of the built-environment.

In conceptualising the areas of the built-environment that have degenerated and therefore may be regenerated, three regions within the public domain can be easily identified. They are: the urban public spaces, the urban housing environments and the sacred spaces and places of cultural heritage. It is not denied that the creation of new venues of economic regeneration such as the harbours, airports, hotels and other such projects will decisively and indisputably contribute to regeneration. Yet they by themselves will not transform those spaces and places that have already being exposed to long periods of neglect, unhealthy practices and unimaginative and inappropriate spatial interventions.

Looking at the urban public spaces, these are in any country, places where the collective spirit of a society comes alive. In fact, it is where ‘the society’ lives because behind the public spaces you find families and individual organisations, homes and institutions. The society is not a collection of families and organisations or homes and institutional buildings. When people go out of their private worlds and come together in the public domain, society comes into being. Public spaces are the ‘dwellings’ of public life. In that sense, what we do and do not do; the streets, the pavements, public squares, the gardens, parking lots, shopping malls, roads, alleyways, and other meeting places, partly define what kind of people we are. If the society has degenerated, then the signs of that degeneration can be seen in these public spaces. The regeneration of public space then, entails the regeneration of the society indirectly, while creating the spatial context for a healthy society to evolve.

In the Sri Lankan context, most public spaces have come into being accidentally, rather than by design.

An open public space may be a gathering spot or part of a neighborhood, a street, an area affronting a waterfront or other area within the public realm that helps people to spend time outdoors individually or collectively and tempt them to return there to rejoice, contemplate and regain their sense of community. They encounter ‘others’ there and learn to recognise that they are both like and unlike themselves. They also learns to deal with them; accept their differences, respect differences and recognise the commonness and publicness of being. Open public spaces promote social interaction and a sense of community; the most rudimentary and quintessential characteristics of being human and indeed humane. Character and form of such spaces indicate the social health and well-being of people living behind closed doors surrounding these places and elsewhere.

In the Sri Lankan context, most public spaces have come into being accidentally, rather than by design. They are also in such derelict state, left to become socially undesired. Most such places do not invite people, do not offer opportunities for leisure and have been abandoned. A simple thing like walking down a street has become blighted by squalor, obstructions, noise, dangers, and is often a dreadful experience particularly in cities. Many other public spaces are no better, although a few still remain joyful and enjoyable by many. While the fear of death and destruction that came to haunt public spaces over 30 years of brutal conflict is partly to be blamed, there are other forces that have made most of them socially undesirable.

While spontaneity is certainly one of the rudimentary birth givers of public spaces, a good public space has to be designed, enhanced by natural and man-made furniture, and kept well. It is partly because no single individual can give shape to it, because no one owns it and no one has the authority to define its shapes and forms by themselves. Undeniably, the architects and designers must come to help shape public space no matter how small or big it is. Designers here do not necessarily mean only those with heavy professional qualifications, but those with a great deal of sensitivity and understanding of the spaces and places and have the innate desire and skills to poetically manipulate spaces and things. For a city to be livable, and to foster great communities, great public spaces are needed. Seeds of great spaces come about spontaneously as well as by planning and designation but most importantly must be nurtured and cared for by means of positive planned interventions.

Great public spaces have many of the following general characteristics:

- Promotes human contact and social activities.

- Safe, welcoming, and can accommodate all: young and old, able and disabled, people of all ethnicities, and religious backgrounds.

- Promotes involvement of the community from its close vicinity in its upkeep.

- Reflects the local culture and becomes a celebrated place for local people.

- Values history, historical evolution, and rejoices in celebrating its past.

- Accommodates and provides for a multiplicity of uses.

- Well-maintained, either by the local population if it is a local place and by the state if a national space.

- Possess unique character acquired through location, history, elements and the ambience present.

- Stems also from design and articulation of architecture: visually interesting, and sensual in all possible ways.

- Loved and cherished by people who come to use them, from the immediate surroundings as well as from distant locations.

While designated large parks or areas amongst large swathes of natural surroundings may be bounded by porous man-made boundaries or walls, in urban areas buildings often form the boundaries of public spaces. Apart from the design of the space itself, the buildings that work as edges are critical to the quality of public space. The power of architecture to create public space or negate them is uncontested. They give character to a place, define the boundaries and also sometimes accommodate the people who are likely to use it. Great places are defined by nature, great buildings, and visually stimulating spaces and objects in the landscape. Great buildings, however, does not mean ‘starchitecture’; the buildings that show off their self image over and above the urban landscape.

In fact, we now know that while architecture of buildings themselves may be spell-bounding, that does not necessarily mean that they will contribute to positive public space. The case in point is that of the world renowned architect Frank Gehry’s new buildings (such as Bilbao, and those in Düsseldorf, Germany), which are hailed as great buildings, but have also been destructive on the public space and the streetscape. Instead of starchitecture, we need architecture that recognises urban design with community consciousness. What happens where the building meets the street is critically important to the health of our neighborhoods. Regenerating Sri Lanka needs revitalising the urban public spaces, such as those which have fallen sick in places like Colombo and other locations, and creating much newer ‘healthy places’. Humble and sensitive architects are needed to intervene.

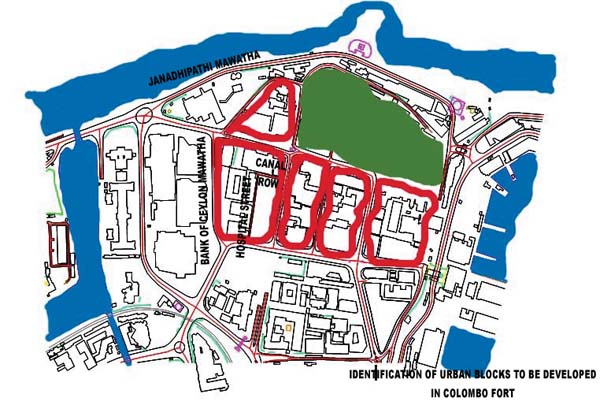

When we come to talk about the developments of Colombo for instance, reference is often made to the idea that Pattrice Geddes conceived in creating Colombo as a Garden City, in which the creation of green public spaces has been a central strategy. We all know that apart from few avenues left around the Colombo University and spaces in several other locations, inappropriate planning interventions over the years and insensitive closed buildings on their edges, have done away with the opportunities to sustain them. If we were to regenerate Colombo as a garden city, which the present approach to ‘beautification of Colombo’ seems to suggest, a lot has to be done by means of first identifying where such open spaces still prevail, where the opportunities to bring back such glory resides, and what new strategies need to be adopted in transforming Colombo’s urban public space. Same can be said about the cities in the regions, which have been losing their great places that people cherish where any opportunities to create new places have been consumed by new developments and urban commercial and residential squatters. Removal of ugly boundary walls abutting streets necessitated largely by the 30 years of terror and subsequent fear is undeniably a great start, but a lot more can be achieved if we commit ourselves to looking deeper into the nuances of public spaces and understanding how to create great places.

In order to delve into these issues, and to draw attention to the poverty of the degenerated urban public spaces around us, the Sri Lanka Institute of Architects has dedicated a session at the Annual Architecture Conference -2012, solely for the revitalisation of the urban public space. It has also invited as a key note speaker, one of the most renowned architects, Jan Gehl of Jan Gehl Architects of Netherlands, whose specialty is the creation of public place and has been criss-crossing the globe and inspiring city authorities everywhere to re-orientate their energies to make great places which we can all cherish. His insights will be cross-bred by our own urban designers who will, at this Architect-2012, bring to light how we may revitalise our urban public spaces and contribute to the regeneration of Sri Lanka.