-

The Ambalama

October 2009

a condensation of our building tradition

“We have a marvellous tradition of building in this country that has got lost because people followed outside influences over their own good instincts…” voiced the world renowned architect Geoffrey Bawa (2002), who in the late 60’ through and up until his demise yearned to bring contemporary relevance to age old traditions in Architecture.

By Nilooshi Eleperuma

Architecture, engaging as it does with the many and varied levels of meaning in today’s multi-cultural context, it is wise to look deep into our own roots, to try and understand the fundamentals of the inherent culture of the people for whom we attempt to create design solutions.

Detailing, an important concept of architecture, plays a pivotal role in bridging this much needed gap. Although misused and misunderstood, the potential of the detailing tradition of most art forms in Sri Lanka can add much to positively influence contemporary design. Such potential however, must be uncovered at the level of cause and motive rather than on its effect and form. Traditional disposition does not simply mean continuation of or reliance on the achievements of the past, rather, the successful application and adaptation of new interpretation.

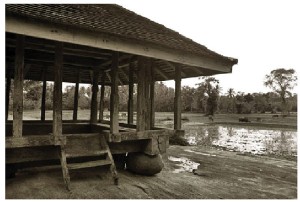

Sri Lankan traditional architecture like any other architecture is the expression of a particular era, the era that produced the noted Ambalama and Devale structures. The Ambalama or the resting place of the wayfarer is one structure that best externalised the beliefs and aspirations of the successive societies.

Buildings in the past were not treated as objects of static sculpture, unlike the much acclaimed modern movement trends which surfaced later, globally. The traditional buildings appeared to move and grow with the possibility of spaces being added to or altered if and when necessary.

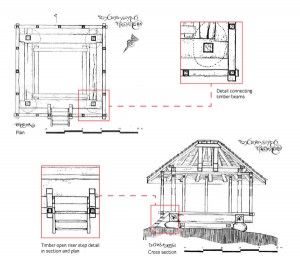

Many of the fundamental principles of the building tradition of Sri Lanka are condensed in the small structure of the Ambalama. The Ambalama appears as if the structure could be picked up and carried away and has been brought and left here in a similar manner. The timber beams were halved by deep notches and fitted together, with the intension of crossing the beams rather than ending them at an edge. While meeting of the two beams at their edge would emphasise a square; finite geometry, in a typical modern movement detail, the beams of the Ambalama meet with a stagger of at about 2”- 3” at all corner points of the structure, implying continuity.

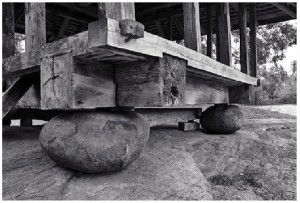

In the detail of connection between the timber and stone, the stone and ground plane, is again an expression of impermanence. The stone sits upon the ground plane in much the same way it would, had it not been utilised to transmit the load of the Ambalama. And the timber structure is simply kept upon the stones.

A light, inclined, timber step ladder provides entry to the Ambalama instead of the convenient use of a stone similar to that of the footing stones.

The footing stones although a part of the structure maintains a predominant visual relationship with the context. The non-permanent bondage of structure with the ground plane expresses the temporariness of its construction and more importantly its presence; the structure occupies this space only for a moment.

The organic form of stone and ground plane in contrast with the square plan form and geometry of construction express the discipline of approach. This idea of non-permanence is fundamental to Buddhist philosophy, the predominant religion in the local culture. This deep rooted norm of uncertainty has evidently influenced the architecture of this day and age. Thus the local culture accepts death and deterioration in a manner, quite unlike the Western perception of death being due to a simple accident in theosophy.

Consequently the building practice subtly reveals the psychology and thought process of its designer; buildings are built knowing they will perish. Although it was not so deliberately thought out then, it is important to consciously scrutinise such expressions now, as external influences to the local tradition are many and the core values of ones own tradition are hardly sought to be identified. Merely scratching the surface of the tradition of built aesthetic in Sri Lanka, is both inadequate and inappropriate. Barbara Sansoni, a local designer who thrives to bring to life lost traditional arts and crafts surmises, “Society and architecture were once hedged around with rules which had to be followed; many of them were not recorded or described in literature, but this does not mean that they did not exist, rather that they were so fundamental as to be implicit, unwritten and correspondingly inviolable. It is a mistake to think that rationality was not a part of traditional architecture.”(1988)

In this sense tradition is a constructive force recognised for its timeless merit in establishing a culture that would give the present its own significance. It is fuelled by the hope that buildings can once again find their roots within the society for which they are produced.

Sometimes I’d go to see old religious sites with ancient temples. In some places they would be cracked. Maybe one of my friends would remark, “Such a shame, isn’t it? It’s cracked.” I’d answer, “If they weren’t cracked there’d be no such thing as Buddha. There’d be no Dhamma. It’s cracked like this because it’s perfectly in line with the Buddha’s teaching.

Ajahn Chah, 1994