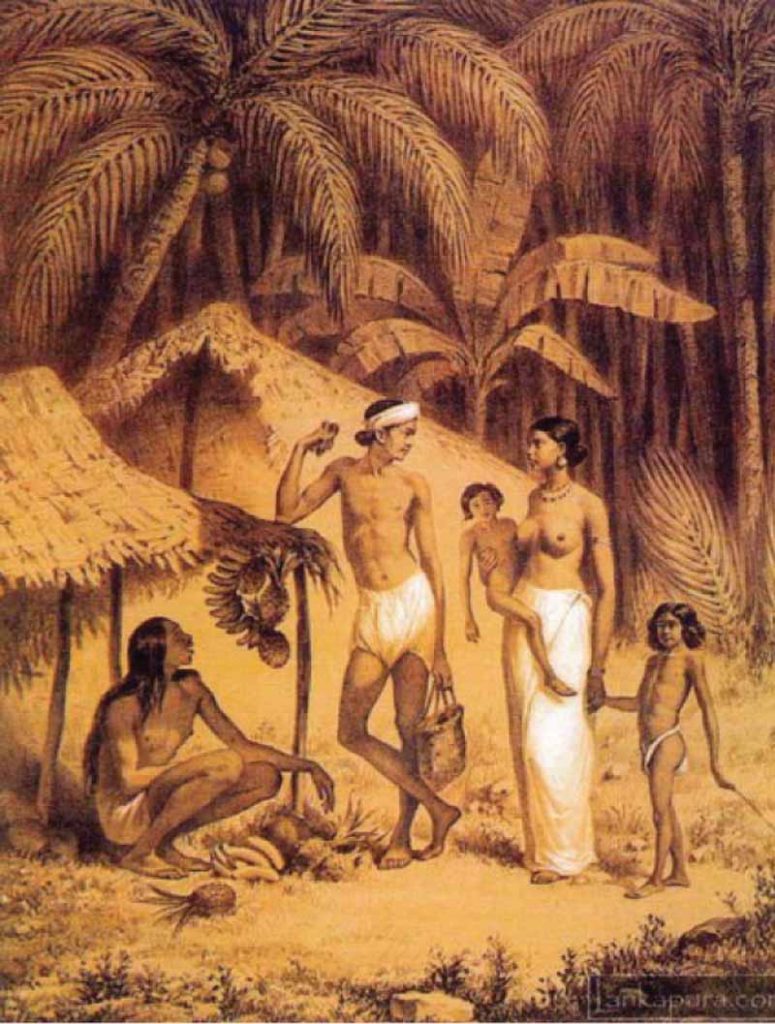

Rural wilderness of rapidly globalizing Sri Lanka is fast becoming an image of a romantic past; glimpses of a forgotten time when the colonial travellers were mesmerised by the lush green of the Island’s dense jungles, encountered its wild beasts and strived to conquer a secluded hilly kingdom called ‘Kandy’ fiercely protected by a “moral” people who were “not war-like”. Such exotic images were captured vividly in the travel writings of numerous colonial officers and priests. Since the progressive ‘village re-awakening’ (Gam Udava) programme implemented from the 1980s, the residual images of the pre-modern Lanka undoubtedly started to vanish fast, along with its gentile architectural heritage and imagery.

By Archt. Dr. Nishan Rasanga Wijetunge

Since the days of ancient kings of Lanka, only the Royal palaces and the religious establishments (viharas and Devales) enjoyed privileges of continuing the ‘high’ culture of the land via the practices of its ‘grand design tradition’. The medieval Kingdom of Kandy is considered as the last Sinhalese bastion of culture before modernity where Royal edifices from the Dalada Maligava to Ulpenge manifest hints of the finer archaic building traditions of the land, despite being tainted by centuries-long architectural traditions that infiltrated the highlands from the colonial maritime. Yet, the residual architectural traits in them—from the ‘classical’ to ‘medieval’ times— could still be envisaged. Most of the Buddhist religious edifices such as Malvathu and Asgiri Viharas built paralleling the colonial stint of almost half a millennium, suffered the same fate. However, the dwellings of faith from the former Kandyan regions such as Lankathilake, Gadaladeniya, Degaldoruwa and Ambekke—and their assorted building types such as stupas, image houses, banquette halls etc—as well as the secular building types such as Ambalama managed to remain more or less in their original forms.

Out of the handful of non-secular building types that escaped unscathed the colonial architectural onslaught, the Tampita Vihares (Buddhist image houses on pillars) are the most noteworthy. Usually perched on raised stone pillars, these elevated structures possess timber floor platforms and wattle and daub walls supporting a timber framed roof covered in flat clay tiles. Mostly conceived to have square plans, they usually have a narrow verandah circulating the main enclosed space in the centre that protects lime stone/timber Buddha statues. Their roofs are two-pitched, walls are white washed, timber work (door/window shutters, rafter edges, balusters etc) carved and internal walls painted with murals; manifesting some of the key distinctive characteristics of Lankan high cultural edifices. Mostly seen in Kandy and Kurunegala districts, most of the Tampita viharas in fact, date back to the 16–17th centuries.

Out of the handful of non-secular building types that escaped unscathed the colonial architectural onslaught, the Tampita Vihares (Buddhist image houses on pillars) are the most noteworthy.

In terms of secular buildings, the Hatara-endi-ge, mostly found in Kandy and Matale, is the intermediary building type that epitomises the dialectic between the ‘grand’ and ‘folk’ architectural traditions. Being an introvert blank-walled structure with a square plan and a central courtyard surrounded by wide verandahs, its plain interior with minimal space divisions (one or two rooms at best) suggest the lack of hierarchical ordering within the family; perhaps induced by the way of life of the Buddhist occupants. The men, women and children spent time mostly in its front area (maha maduwa), while cooking was done at the back (heen maduwa). Raised on a high masonry plinth, these wattle and daub houses usually had roofs of timber, thatched with straw. Usually equipped with doors on opposite sides of the plan, windows were found seldomly. The houses were modeled not as retinal-centric structures that please the eye, but to co-exist with Nature and to return back to it at the end of their life span; indeed acknowledging the sense of worldly impermanence advocated by the Buddhist doctrine. In the contemporary times, while it is a daunting task to find examples that have survived the onslaught of time and change, the one in Medawala, Kandy is a fine example.

While these were the houses of Kandyan sub-elite, the elite at the apex of the social hierarchy lived in the ones configured by repeating the generic Hathara-endi-gedara plan—an extensive ‘Wallauwe’ with external blank walls and multiple courtyards. While many found today have been altered to possess colonial-type colonnaded façades, Aluvihare Maha Wallauwe in Matale has somewhat preserved its original features.

The houses were modeled not as retinal-centric structures that please the eye, but to co-exist with Nature and to return back to it at the end of their life span…

On the other hand, the house of the common man was much simpler; a humble wattle and daub hut with a rectangular plan form (with one or two internal room divisions), a raised plinth, front-facing verandah called pila and an overhanging thatched roof. The plan configurations and outlook of these austere vernacular buildings varied slightly in each climatic zone within the Kandyan territories, according to regional micro climates and material availability. This vernacular tradition going back to ancient Anuradhapura times was utilised to erect houses of the work force of the nation; toiling to make ends meet, while nourishing the religious establishment that ideologically fed society as well as a political system that safeguarded the prior through their generated surplus.

Together, this vernacular and other finer forms constituted the heart of the Sinhala architectural identity, which in the contemporary times is hanging by a tread. It is indeed, the utmost responsibility of all Sri Lankans to do their part to safeguard these endangered legacies for posterity. Ruskin once discerned architecture’s ability to constitute a national identity in its didactic capabilities. If we do not safeguard our lingering gentile architectures as such, the authentic Lankan identity would be irreversibly lost forever.