-

Timber in Medieval Sri Lankan Buildings

October 2010

Timber is one of the most popular and perhaps the earliest building materials in the history of world civilization.

By Shobha Seneviratna based on an interview with Professor Nimal de Silva

The tradition of wood construction in Sri Lanka is seen in the pre and post historic periods, specially in association with cave shelters. Timber construction has been used in the front portion with wooden doorways and window openings and wattle and daub partitioning.

Timber construction developed and gradually reached a state of sophistication. The original concept of timber posts developed to square or eight sides, but was still buried in the brick walls of the building. Nevertheless, as time went on, the post and beam style developed to a highly decorative form of architecture.

Historical evidence reveals the existence of sophisticated wooden buildings dating from the 3rd Century. The massive timber doorposts at Sigiriya are all that remains of an elaborate gatehouse made of timber and brick masonry with multiple tiled roofs.

In structures like the timber gatehouse at the eastern entrance to Anuradhapura built in the 4th Century BC frames made out of whole trunks of trees carried the entire weight of the building. The vertical crevices in the brickwork, where such wooden columns carried the load of the upper floors and roof, can be seen in the remains of the palaces at Polonnaruwa and Panduwasnuwara. These openings still retain the spur stones upon which the wooden column once stood.

Ancient records reveal the strict traditions that were observed during the cutting and seasoning of wood in earlier periods. Mature trees were selected and cut in the new moon when the sugar content in the timber was lower, so that destructive wood boring insects were not attracted to the timber. The stone remains indicate that the axe, adze and chisel were the common tools used in timber work.The Saddharmarathnavali mentions two carpentry practices where oil was applied to timber to prevent decay, and heated to straighten it. The timber selected for decorative purposes and carvings often had the properties of durability and easy workmanship. Gammalu (Pterocarpus marsupium) and Halmilla (Berrya amonila) were commonly used for structural components and are also found in the beautifully decorated buildings of the Kandyan period.

The excellence of timber architecture in Sri Lanka is well expressed in many building forms. Among the masterpieces of timber architecture preserved to this day are the simple Ambalama wayside resting places, the storied shrine rooms and also the wooden bridges such as the Bogoda Bridge.

Timber sections used in the timber architectural forms such as the wooden beams, brackets and pillars were of heavy, large and bulky sections. In Kandyan timber architecture these have been made aesthetically appealing and lighter by beautiful, elaborate wood carvings and decorations. Kandyan timber architecture which has a distinctive character of its own dates from the Gampola period (1341-1415AD).

The timber architecture of the period reveals the extensive range of timber joinery developed. These include dove-tailing, mortise and tenon and halved joints for large beams. In the simple rest hall or Ambalama, the pillars are fixed with crossing timber beams with halved joints. The large beams are joined by a sort of scarf joint and is cleverly executed.

In some buildings, timber was used extravagantly. Large sized and whole tree trunks were left round, untrimmed and roughly cut. An example is found in the Bogoda Wooden bridge which has three trunks and beams and supported in mid stream by two large tree trunks which acts as a pier.

The Drumming Hall in the Ambekke Devale, The Audience Hall and the Temple of the Tooth in Kandy, Degaldoruwa temple in Malwatte and the Panavitiya and Mangalagama Ambalamas are well preserved examples of the wood carver’s craftsmanship and art.

The structural frame of the Ambekke Devale, consists of two pillars on either side connected by beams and capitals and connected on top again with a series of large beams. These structures, beams and the rafters of the simple gable roof have been richly carved. The ridge plate ends in a king post to take the corner rafter of the front end and the giant pin or the Madol Kurupawa.

Some of the finest examples of wood carving of medievel Sri Lanka can be seen in the Ambekke Devalaya. The exquisite craftsmanship can be seen in the carvings on the medial panels of the pillars and also the cross brackets, with their drooping lotuses forming the capitals of three pillars.

The Audience Hall is built on a raised stone plinth that is in two levels. The timber columns are arranged in four rows, two on either side, with a total of sixty four carved columns. The rafters are carved and deeply notched. The capital or the pekadas are carved with inverted lotuses. The dominant roof structure consists of elegantly carved beams and rafters forming a hipped roof. The wall plates are elaborately carved and the supports are carved at terminals.

Many of the multi-storied Buddhist shrines are in the Kandyan period and have a general timber framed structure with a considerable amount of masonry or wattle and daub walls. The Temple of the Tooth, Kandy is the finest example of this type.

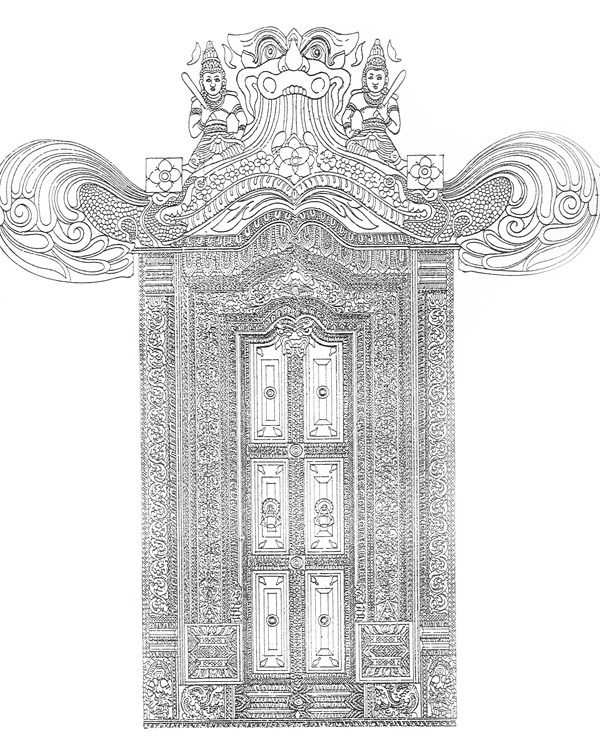

In most buildings of the medieval period the doors and windows were of timber as well. They were fitted and pegged together and built into the walls. Door jambs were often carved intricately. Door sashes are secured with beautifully designed timber locks. The windows of the medieval buildings were of two types. They were either the exact version of the timber doors but to smaller scale or fitted with lacquered wooden bars.

The designs used for the carvings in medieval buildings are generally common to all Sinhalese art. But special care has been taken to treat them in a manner suited to the practical material. Great relief is seen on the liya wela ornament of door jambs, and the carving of pillars, capitals and bolts. A characteristic feature is the emphasis of the outline of stems or interlaced works with an incised line next to the margin on each side. However, wood carving that is completely round is rare in mediaeval buildings.

The decorated motifs used in the carving found in medieval buildings are of many forms such as geometrical designs. Carvings on the panels of wood pillars of Kandyan buildings have a geometrical layout. Floral patterns, the lotus is the commonest floral pattern used in wood carving, with great deals and variations. The most characteristic, the simple lotus forms are the “rosettes,” used to fill the space between.

The male and female figures have been depicted in scenes from day-to-day life in wooden carvings. Singers, drummers, soldiers, dancers and wrestlers are among some of them.

Among the animal motifs are elephant, lion, horse and bull. The peacock and the swan are the most commonly found of the birds in the wood carvings. A mythical bird, in the form of double headed eagle (berunda pakshiya) is also seen.

The sarapendiya and kihibi muhuna are both mythical motifs, vakadea motif consists of two simple curves which in many combinations make up a pattern. The lanu gataya motif depicts a knotted rope. It is generally used for borders or as a filling in the centres of square panels.

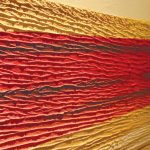

The craftsmen of the period also used several other techniques to decorate the timber buildings during the medieval period. Painting, lac-work, inlaying of timber with metal, carved ivory and different colours of timber and guiding were some of them.

Both structure and non structural materials were decorated by painting. Painting often not only complimented but also acted as a protecting layer for the timber. It was a common practice to leave the carvings on the columns, brackets, beams and rafters unpainted while decorative icons – specially the ceiling and balustrade were painted in many traditional designs. In the Sinhalese tradition before painting was done on a carved decoration or icon, a thin layer of kaolin mixed with vegetable glue was applied as a primer.

The timber constructional tradition has developed and perfected for over two thousand years. It shows the contribution to our culture made by the genius of the ordinary and anonymous carpenters, joiners and wood carvers during the medieval period. These well preserved masterpieces of wooden architecture prove that timber is one of the most suitable building materials for Sri Lanka. Even though it is no longer so freely and abundantly available for total timber construction, a sensitive incorporation of it is still possible.

- Ornamental Timber Doorway, Padeniya Temple, Kandy

- Bogoda Bridge, Badulla

- A wayside Ambalama

- Different carvings in medial panels of the pillars in Ambekke Devale

- Madol Kurupawa with 26 rafters in Ambekke Devale

- Carving on underside of pekada in Ambekke Devale

- The Audience Hall Kandy

- Sectional drawing of the Temple of the Tooth, Kandy. Other examples are the shrines at Ambekke Devale Vegiriya, Budumuttava, Dambadeniya

- Carvings of soldiers and dancers

- Carvings of soldiers and dancers

- Carvings of birds

- Carvings of birds

- Painted timber beam as bracket, Temple of the Tooth, Kandy