-

Lessons Of Yore: Strolling Down Memory Lane…

October 2012

It is certainly not another typical campus day for a team of first year students of the faculty of Architecture. The group gathered at the terminal, boards a bus from Colombo that heads towards Kandy, and beyond the Hill capital to Matale. They eagerly expect finding the two roadside buildings along Kandy-Matale road which their first year lecturer described as “beautiful”. The students by now possessed enough skills to visit a built structure and make a measured drawing from the information gathered on site…

It is certainly not another typical campus day for a team of first year students of the faculty of Architecture. The group gathered at the terminal, boards a bus from Colombo that heads towards Kandy, and beyond the Hill capital to Matale. They eagerly expect finding the two roadside buildings along Kandy-Matale road which their first year lecturer described as “beautiful”. The students by now possessed enough skills to visit a built structure and make a measured drawing from the information gathered on site…

By Zeena Marikkar

What we were required to do on site was to measure each and every facet of the building and develop a quick sketch; every horizontal measurement, every vertical measurement, every angle, and how it all formed one whole; the “beautiful” building. The proper ‘two dimensional drawing’–as it is called, was to be drawn once we returned to Colombo, in the faculty studios. Although digital cameras that allowed unlimited shots were not in our reach then, the thirty six film saviour helped us immensely to record the building in its minute detail.

The Kandy-Matale road is bordered by the river on one side and the hill on the other, still thick and green. It was not difficult for us to find the two pleasant looking buildings along the road, just as we drove past the 8th mile post from Kandy, in Akurana. These were neither massive nor complicated structures, but pleasing to the eye non-the-less. We nodded approvingly of the befitting account our teacher had given us. The fact, that perfect ratio, of height, width and length, closed and open areas of buildings lead to structures that are ‘well proportioned’ or pleasant to look at, is a reality we learned in our lecturers much later.

After a brief survey, we divided ourselves into two groups to measure the buildings. The two structures, on either side of the road, were built in distinctly different ways. The building close to the river had a long face and a slim cross section. This fitted perfectly in the narrow flat surface beyond the road to the top of the river bank. The other was with a lean frontage and a deep section. The end of the building was almost plugged into the mountain slopes. Our group was to document this building.

While making measurements, it occurred to us that the mountain range sloping towards one of the smaller branches of the majestic Mahaweli River, had been cut, to lay the Kandy-Matale road across Akurana, by the British. Akurana is mostly populated by Muslims. The livelihood of this community had been retail trade as it is now. There is much evidence that this building too had been used for trade. Being sited along the road, away from the interior villages and fully collapsible timber doors at the ground level led us to believe so. We now spoke of the building as a cozy coffee shop that might have helped anyone travelling along the Kandy-Matale road to quench their thirst. The building is of two stories. Wooden planks nailed to a solid timber casing formed the upper floor deck. A step-ladder tucked into a corner served as access while taking up minimal space. Flaking lime plaster revealed the enclosing walls. Walls are of large bricks made of hard, reddish soil, Kabok, possibly gathered from around the site. The strangely thick walls may have helped to keep the interior warm.

A small enclosed area was found at the back of the building. This space had a few raised levels built up with cement; quite an unusual feature, we thought at first. We then assumed the varying levels to be a means of cooking and serving food easily; somewhat of a modern day pantry top. It was not difficult for us to understand that this was also an effective means of stabilising the building structure. The foot of the mountain was plainly ‘made’ to continue in to the building; a retaining wall that’s put to good use.

The cooking space was connected to the upper deck through an opening. Another window brought in ample light and cool breeze into this space and beyond. For someone at the upper level, the aligned windows beautifully framed in the lush green of the Akurana hills. We now recall that this magnificent experience was but the ‘visual axis’, constantly spoken of in describing architectural views.

In addition to the window, high up on the side walls of the kitchen were two rows of circular holes. We assumed then, these holes did what the windows did, and learned later that fan-lights or electrically operated exhaust fans are placed in kitchens to suck out hot air and odor.

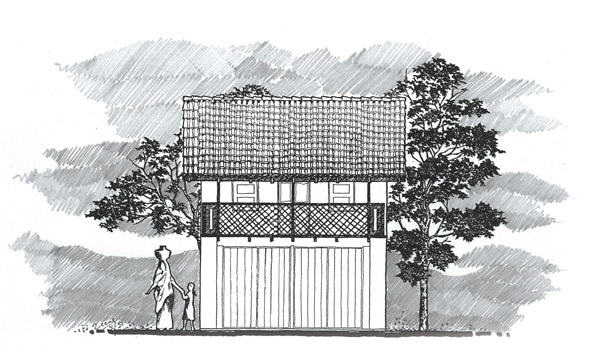

Although with limited knowledge as first year students, we were forced to speculate much of the background information, the buildings’ original purpose, usage, tenants, time period etc. It was not easy to trace someone who knew details of the building. The occupants had already abandoned making use of these, even though the buildings were in good condition by then. The simple gable roof of the building was steeply sloped and covered with local tiles. The short side bared the front façade to the road, and brought in generous light. The longer roof spanned to almost touch the ground at the back. Although Akurana gets reasonable rain, anything akin to the leaf filled PVC gutters were not to be noticed here.

We pictured the rainwater draping down the large eve of the shorter roof and flowing steadily across the road to reach the river. Most of the water during rain, we guessed, would surge down the larger roof, to fill the ‘earthen gutter’ at the end of the building; the natural dent made by constant flow of water along the foot of the hill, was clearly visible. These ‘drains’ paused and connected the valleys. We witnessed for the first time, a simple yet comprehensive storm-water drainage system. The trellised balcony along the front façade, serves to grab the splendour of the surrounding while being screened from the road. This extension also protects the lower level from sun and rain forming an in-between veranda, a much hyped space in contemporary tropical architecture. This wide verandah may have been extensively used for small talk whilst sipping tea. Traces of a raised outside lavatory along with a covered bathing space was seen close to the main building. A bamboo trunk tucked into the hills, disciplined the spring-water gushing down the slopes. The mere thought of a cool afternoon shower under the shade of a tree was enough to give our tiring selves a refreshing stimulant.

Half way through our task of measuring the building, arrangement of the kitchen, upper floor deck, concealed bathing space and the lavatory all subtly hinted at another find. The building in addition to being a shop may have been also a home to a family. Perhaps a family from the interior villages of Akurana decided to make this a shop-house. The mother cooks in the kitchen while the father is busy engaged in the shop… Children play around the house under close watch… The elders relax in the balcony in the evenings without being pored over from the road…

Research reveals that having ones home and place of work within the same compound or at least in close proximity leads to much sustainable living and happy families. Even modern day apartment complexes take this into account when planning for sustainable cities. When dusk fell and it was time to leave, we noticed more shop-houses built along the road, some dilapidated, some still intact. They stood scattered amongst large old trees. Placement of these structures had been clearly worked out to reveal and preserve the untainted beauty of the hills.

Between then and now, each time I drive past Akurana, I invariably glance at the buildings we so lovingly documented. They stand abandoned and haunted. What is left to decay is a window to the rich lifestyle of our forefathers with many lessons to offer. My contentment is that I was able to record at least a facet of that existence. A glass box has now replaced the ‘beautiful’ building. The mannequins forced into it are frowning at the sun. This was definitely not Akurana we experienced a decade ago. Then again, it does not really have to be so. Time can be the best catalyst for development and experimenting. But, the development is most fruitful only if it embodies useful lessons from the past while aspiring to move forward. Climate, physical landscape, socio-economic setting all play a pivotal role, especially in dealing with man’s built environment.

A building, however big or small, mirrors a society’s collective hopes and ambitions as much as it shows how a community lived and its identity. Kandy-Matale road is not different now from any other wildly built up road anywhere in the country.