The arts and crafts of Sri Lanka were famed for the artistic excellence and superb craftsmanship. It forms an integral part of our cultural heritage. Among the myriad array of local handicrafts, lacquerwork is eye catching with its bright colours and exquisite designs.

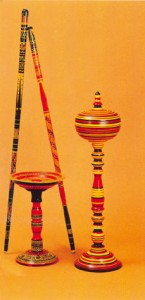

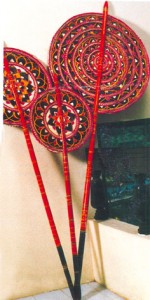

Lacquerwork is identified as a Kandyan craft. Lacquer-painted ornamental windows and railings were a common feature of Kandyan architecture and also provided exquisite decorations for the wooden covers of palm leaf manuscripts, known as ‘pothkumba.’ The Kandy museum’s collection of lacquerwork objects include bows and arrows, handles of spears, banner-poles, headboards and legs of beds and Sesat – the ceremonial sunshades used by the elite in royal and religious ceremonial processions. Lacquerwork is also used to decorate Kandyan drum sets and flutes (Horanewa).

According to Dr Ananda Coomaraswamy, “the lacquer workers were organised into a professional group called ‘I-waduwo’ (arrow-makers). They worked mostly as assistants to the chief craftsmen of the PattalHatara or Four Guilds of Craftsmen. In the hierarchy they are identified as belonging to the lower division of the craftsmen (Achario). Lacquerwork survives to this day as the traditional occupation of the families of the craftsmen at Hapuwida in the Matale district – which is also known as the place where the craft originated – and in a few other places.

“the lacquer workers were organised into a professional group called ‘I-waduwo’ (arrow-makers). They worked mostly as assistants to the chief craftsmen of the PattalHatara or Four Guilds of Craftsmen. In the hierarchy they are identified as belonging to the lower division of the craftsmen (Achario). Lacquerwork survives to this day as the traditional occupation of the families of the craftsmen at Hapuwida in the Matale district – which is also known as the place where the craft originated – and in a few other places.

The traditional method of processing lacquer is long and laborious. Natural lacquer is a resinous substance secreted by a species of scale insects called Lacquer insects (Kerrialacca). They show partiality for certain trees and shrubs, particularly the Keppitiya Trees (Croton lacciferus) where they produce heavy secretions called ‘lakada’ in Sinhala. The twigs are cut and left for some time for the insect to settle. Then the resin is scraped and collected into thin long cloth bags which are heated over a charcoal fire until melted and are then squeezed out by carefully twisting the bags. Mineral dyes of red, yellow, black, and also green are added and mixed with the ‘lakada’ by heating again over a charcoal fire. Today these traditional materials have been largely substituted with imported material. The wood used for turning out various articles is generally ‘suriya’ (Thespesiapopulnea), although the craftsmen use other timber as well due to scarcity of timber.

The lacquer worker shapes and colours an object making use of a simple lathe fixed to the ground. The block of wood fitted to the lathe is turned by means of a bow, while it is shaped by using tiny chisels until it takes the desired shape. Lacquer work differs from painting, in that brushes are never used.

The geometric colouring, which makes the product distinctive, is done using many different methods. The lacquerwork done in Matale is of a distinct type known as ‘Niyapotten-Weda,’ or fingernail work. The colours of red, yellow, black, and green are heated and drawn into thin threads and applied onto the object while using the fingernail to manipulate the design in the required pattern, and then heated and polished with an ola leaf to get the desired effect.

Two other methods of colouring are also used. Layers of three different colours are applied and a pattern scraped on the outer colour letting the shades underneath show through. The outer shade is usually black or green, with yellow and red in two layers under¬neath. The other method is to carve a pattern on a prepared background and filling it with colour.

Two other methods of colouring are also used. Layers of three different colours are applied and a pattern scraped on the outer colour letting the shades underneath show through. The outer shade is usually black or green, with yellow and red in two layers under¬neath. The other method is to carve a pattern on a prepared background and filling it with colour.

Traditional crafts can be used to enhance other disciplines of design, as is reflected in ArchtMinette de Silva’s work where lacquer worked railings and curtain rods have been used to produce a pleasing effect stamped with our culture.

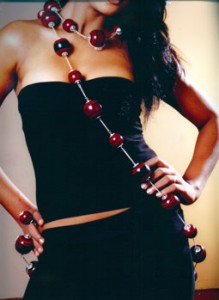

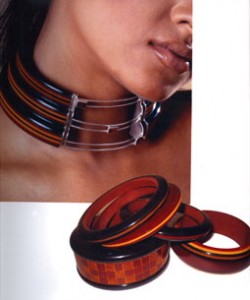

The Bachelor of Design Programme of the Moratuwa University, in an endeavour to introduce new product innovations from traditional crafts, experimented with base materials and the processes and the techniques used in the lacquercraft to create exquisite jewellery with modern designs. It’s hoped that this would eventually benefit the craftsmen and offer the craft a new lease of life.

Adapted from an article by L K Karunaratne. Acknowledgements: Prof T K N P de Silva, Director Postgraduate Institute of Architecture; ArchtHiranthiPathirana, Bachelor of Design Programme, Faculty of Architecture; JayadevaTilakasiri, Handicrafts of Sri Lanka.