-

Landscapes & Asian Cities

March 2008

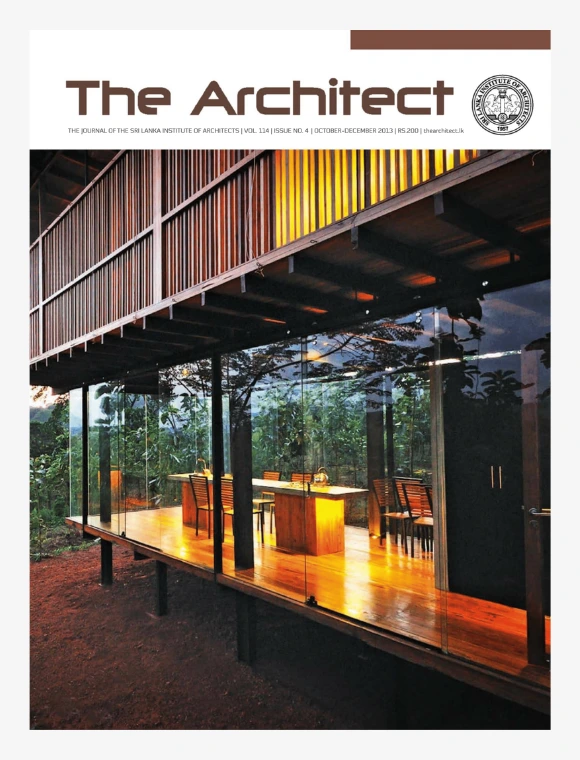

Black and white, yin-yang, positive-negative are some contrasts that bring about a wholesome balance. Such is the outdoor-indoor relationships of a building and its immediate outdoor environment at a basic level. The landscape professional sees the entire city as an urban landscape, while the architect translates the same city to be a built environment.

Black and white, yin-yang, positive-negative are some contrasts that bring about a wholesome balance. Such is the outdoor-indoor relationships of a building and its immediate outdoor environment at a basic level. The landscape professional sees the entire city as an urban landscape, while the architect translates the same city to be a built environment.

By Archt. Shereen Amendra

Cities are artificial constructions which have been around from as early as the 8th century B.C. in Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka. Modern megalopolises have since arisen all around the world, with many large cities in the Asian region. However, most inhabitants of these cities have had their roots in rural landscapes and welcome a fresh breeze and soft green vegetation to relieve the long indoor hours. This is just one of the contributions of city landscapes. The environmental contributions alone are vast, in addition to the aesthetic, functional, spatial, psychological – and particularly in Asia, the spiritual aspects.

All these aspects are intrinsically linked. The city dweller’s need for health and well-being, leisure and recreation is imperative for optimal output at the workplace. An early morning walk, a jog or as in cities of China or India, a session of tai-chi or yoga exercises requires pleasant outdoor landscapes. School children in the city may receive an education in urban woodlands and designated ‘wild’ outdoor spaces. Singapore’s river rehabilitation programme has introduced ‘wild’ landscaping on its river margins, contributing to nature study while cleansing the water and providing a habitat for fauna in the city. Colombo, with its high percentage of wetlands, has similar potential for scattered urban nature parks.

Heritage landscapes in cities are important reminders of a city’s growth and historicity. The British-colonial influence in these cities, with cricket grounds, lawns and mass planting, has pervaded these landscapes. Colombo and Galle are such ‘recent’ cities in Sri Lanka, while centuries old Anuradhapura was intrinsically linked with the landscape of wewas (artificial lakes) edged with a raised bund and fringed green with vegetation. The adjacent parks, the Mahamevna and Nandana had particular trees on raised platforms (malaka). Mediaeval Polonnaruwa had similar landscape elements and was yet so different in its detail and ornamentation.

Heritage landscapes in cities are important reminders of a city’s growth and historicity. The British-colonial influence in these cities, with cricket grounds, lawns and mass planting, has pervaded these landscapes.

The movement of peoples across continents, and their influence on city landscapes are evident the world over. The establishment of botanic gardens in the tropics brought many trees and plants from other countries to further enrich indigenous flora for landscaping the open spaces of Asian cities. The soft shade and wide canopy of Samanea saman (Rain tree) from Africa, undoubtedly selected for its large stature in keeping with the city architecture, is now naturalized in Asia.

In Sri Lanka, the urban gardens of community residential areas, mainly comprising people attracted to the city from the countryside, echoes the home-garden of their village. These charming home-grown landscapes sport vegetables and fruit trees which contribute to both an economic sustainability and food security.

Many areas of the city with a particular significance or purpose are often complemented by an appropriate landscape design. Ambience, historical value and a sense of place are largely dependent on the visual imagery of the landscape. For example, formal avenues with disciplined sidewalks and straight roads lend themselves to grand public ceremonial spaces.

Many areas of the city with a particular significance or purpose are often complemented by an appropriate landscape design.

In contrast, Colombo, designed as a garden city with sinuous interconnected green spaces with trees grown in their natural forms, is conducive to a comfortable homeliness. The pattern of the city’s built area is often a result of the landform and dominant water bodies in its landscape. Port cities spread from sea-board thinning out inland, hill townships hug the mid-slopes with natural streams and lakes. Flat land with no dominant feature ends up as a grid.

Asian cities have similar climatic patterns to contend with, the monsoon rains affecting mainly the South Asian and Southeast Asian cities. Water (and drainage of excess), green lush vegetation, a salubrious climate between bouts of lashing rain and high humidity contrasted with a vibrant dry season and Asian festivals are factors the landscape architect has to contend with when approaching a design project.

With climate change and sustainable design being high on the list of priorities, the ‘greening’ of the environment now often takes precedence in the overall landscape design. Stormwater moderation is assisted by the extent of landscaped areas under vegetative cover and drainage through careful attention to slopes and grades, the use of swales, ditches and French drains as appropriate coupled with aesthetic and functional retention areas. However, the intensity of rainfall in monsoon Asia appears to have increased with a necessary re-think in design strategies.

Climatic and temperature moderation, considering the high insulation of the tropics, takes into account the use of surface materials and shade characteristics – with tree canopied areas, grassed surfaces and gravels preferred to vast areas of concrete paving. High seasonal winds mean a higher preference for deep-rooted trees in groups rather than in isolated avenues giving the characteristic Asian casualness. New challenges are pollution filtration needs and trees as pollution indicators.

A major aspect of successful city landscapes and their viability go beyond the concept and design to also include responsible management of these outdoor areas.

The South Asian system of Shilpa shasthra ensured that trees were not cut or pruned as it would harm the living plant. A system of horticulture called Wrukshayurveda determined how plants should be managed. While many cities around the world manage their trees by pollarding, crown lifting and thinning to control size and shape, plants in Sri Lanka have minimum intervention allowing natural growth according to our culture. This allows for a more informal outlook without stereotyped shaping.

Further, the culture of the people must be clearly understood – unlike westernised parks with outdoor seating areas, food kiosks and interactive spaces, the inherent habits of Sri Lankans are that they do not usually eat outdoors, nor openly display affection and in the city rarely gather outdoors (other than to demonstrate a cause). Such activities have been habitually indoors or at least in a pavilion. Those romantic lovers who dare, create their own privacy behind an umbrella if the landscape does not afford it.

Differences abound. Asian cities have low resident populations compared to the daily floating population drawn from suburbs or nearby townships. Many Indian cities use bicycles, whereas Sri Lankans rely mostly on public transport, requiring pleasant gathering spaces near such transport centres.

As more Asians travel abroad and as globalisation spreads, a change is evident in lifestyles and attitudes, requiring more aesthetic and efficient outdoor spaces.

A major aspect of successful city landscapes and their viability go beyond the concept and design to also include responsible management of these outdoor areas.

Local authorities must necessarily look to public-private partnerships to ensure effective maintenance of city landscapes. The infrastructure of the city, underground or overhead, should give due deference to the aesthetic and functional requirements of the landscapes they occupy. Landscape management is in turn dependent on water, power and lighting and availability of trained personnel in landscape management and urban forestry. The regular upkeep of hard landscape items such as benches, chipped steps, uneven paving slabs, removal of outdated posters and banners and protective painting can go a long way towards avoiding a degraded landscape.

The beauty of year-round usable landscapes with a refreshing naturalness, most often provided by the sea, hillsides, lake or trees, is what makes Asian cities liveable and which popularise many Asian cities as a humanized landscape and ‘enchantment for the mind, body and spirit’.

Landscape characteristics of a few Asian cities:

• Anuradhapura – green fringed lakes and historic stupas

• Bangalore – containerized plants form masses of landscape ‘planting’

• Chennai – bicycles are abundant on the roads, longest sea beach in Asia

• Colombo – lush green vegetation and salubrious climate, cosmopolitan

• Galle – brisk sea breeze, dominant Fort, bays and coastal structures

• Hong Kong – a compact city – outdoor spaces wrap around buildings and flow through them, many parks

• Kandy – historic city, a valley ringed by hills, host to a high diversity of exotic and indigenous flora

• Karachi – a dry-arid landscape of feathery trees a backdrop to ornamented colourful buses

• Shanghai – multi-tiered ‘the Bund’, river traffic, vast scale

•Singapore – vibrant colour and ultra-neat landscaping

What can be done to improve landscapes?

• Professional landscape design and implementation

• Regular monitoring by landscape management unit

• Prevent further encroachment of public open space

• Ensure open space component of private premises

• Maintain in good condition steps, paved areas, edges, street furniture (all hard landscape components)

• Ensure utilities are in working order.

• Regular inspection and removal of old posters, banners

• Solid-waste management

• Hoarding control

• Tree management under urban forestry programmes

• Set-up tree farms and horticultural nurseries.